Setting Up Server Side Rendering with React, Redux, and Django

At Meural, we decided to implement server side rendering in order to increase our SEO exposure and to make social media sharing more effective. In this post, I’ll talk about how server side rendering works and the implementation that I developed.

Background

In traditional web applications, web pages are rendered on the client side. The browser receives a blob of JavaScript from the server, processes it, and paints the UI that the user sees. In server rendered applications, on the other hand, the first render of a web page is done on the server. The browser receives a pre-rendered page, which it can display without running any JavaScript. This enables better SEO exposure, since many web crawlers cannot run JavaScript, and faster perceived page load times.

There are also some downsides to server side rendering. These include slower server response time and, in lower bandwidth environments, slower time to interactive. For apps that run behind login screens, whose content is private, these downsides might make server side rendering less than worthwhile. For our use case, however, the benefits well outweigh the costs. Most of our app’s pages are public facing, so exposure to web crawlers is essential.

Preliminary Considerations

Implementing server side rendering is not a trivial task. In response to this fact, a number of libraries have emerged to make implementation a bit easier. These include Next.js, Razzle, numerous boilerplates, and others.

These libraries and frameworks can be a good choice for rapidly prototyping a feature or when starting a new app, but I would not recommend them for use in production or for extant apps. The reason for this is that using them requires surrendering a large portion of your codebase to them, which makes debugging and optimization more difficult, if not impossible, and makes you ignorant of how your app is really working. What’s more, integrating such a framework into an extant application is often more trouble than it’s worth.

Therefore, I developed a custom implementation of server side rendering at Meural. I hope that our stack is similar enough to that of other companies so that other developers might find this article useful. Our frontend uses React, React Router 3, and Redux, while our backend is a monolithic Django application.

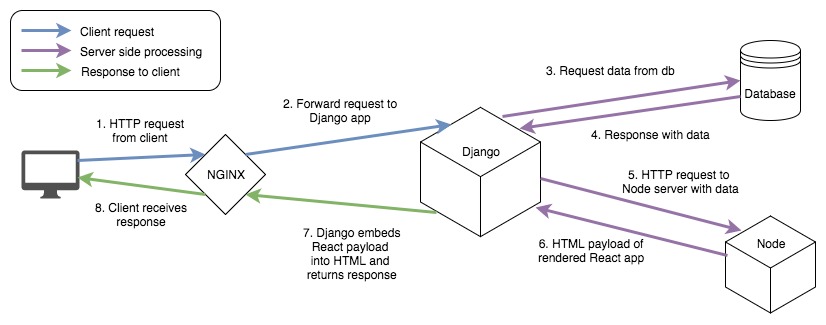

The High-Level View

At a high level, setting up server side rendering consists in setting up the following chain of events.

Since our primary application server is a Django application, which cannot understand JavaScript, we need a JavaScript runtime to render our React frontend. For this, we’ll use a Node server. When a request hits our primary Django server, we’ll query our database to get the info we need. Next we’ll send that info in an HTTP POST request to our Node server, which will return our markup, plus the final state of our Redux store. Finally, we’ll embed this information into the HTML response of our Django app and send it to the client.

Node-Django Interaction

Let’s begin by setting up the Node server. I decided to use Express.js because it is battle-tested and very easy to use. Note that we are reading our NODE_HOST and NODE_PORT variables from our runtime environment.

// server.js import http from 'http' import express from 'express' import bodyParser from'body-parser' import morgan from 'morgan' import { buildInitalState } from './utils' import render from './render.jsx' const ADDRESS = process.env.NODE_HOST const PORT = process.env.NODE_PORT const app = express() const server = http.Server(app) // I've increased the limit of the max payload size in case a huge page // needs to be rendered app.use(bodyParser.json({ limit: '10mb' })) // Morgan is the very silly name of some logging middleware. // It logs requests to the console so that you can tell that // the server is doing anything. app.use(morgan('combined')) app.get('/', function (req, res) { res.end('Render server here!') }) app.post('/render', function (req, res) { // We know we'll need a path and the data for our initial state, // so let's save this stuff first const url = req.body.url // This function massages data into the shape of our Redux store const initialState = buildInitialState(req.body) // We haven't written this function yet, but we know what we want // its signiture to be const result = render(url, initialState) res.json({ html: result.html, finalState: result.finalState }) }) server.listen(PORT, ADDRESS, function () { console.log('Render server listening at http://' + ADDRESS + ':' + PORT) })

I recommend writing a simple render and buildInitialState functions for testing purposes that simply return some valid output of any kind. I also recommend testing this server with cURL before moving on to anything else.

Now let’s wire up the Django app and test its interaction with the Node server.

# views.py import requests from django.conf import settings from django.shortcuts import render from sandwich.models import Sandwich from sandwich.serializers import SandwichSerializer from user.serializers import UserSerializer def sandwich(request, id): try: sandwich = Sandwich.objects.get(id=id) serializer = SandwichSerializer(sandwich) sandwich_data = serializer.data except Sandwich.DoesNotExist: sandwich_data = {} # The magic happens in our _react_render helper function return _react_render({'sandwich': sandwich_data}, request) def _react_render(content, request): # Let's grab our user's info if she has any if request.user.is_authenticated(): serializer = UserSerializer(request.user) user = serializer.data else: user = {} # Here's what we've got so far render_assets = { 'url': request.path_info, 'user': user } # Now we add the sandwich. We use the Dict#update method so that the # key could be anything, like pizza or cake or burger. render_assets.update(content) try: # All right, let's send it! Note that we set the content type to json. res = requests.post(settings.RENDER_SERVER_BASE_URL + '/render', json=render_assets, headers={'content_type': 'application/json'}) rendered_payload = res.json() except Exception as e: ... # Beautiful! Let's render this stuff into our base template return render(request, 'base.html', rendered_payload)

Here’s how we insert the rendered HTML payload into our Django template. Note that we use Webpack and django-webpack-loader to handle our client-side JavaScript.

<!-- base.html --> {% load render_bundle from webpack_loader %} {% load webpack_static from webpack_loader %} <!DOCTYPE html> <html> <head> <meta charset="utf-8"> <meta http-equiv="x-ua-compatible" content="ie=edge"> <meta name="viewport" content="width=device-width, initial-scale=1"> <title>The Finest Deli</title> {% render_bundle 'bodega' 'css' %} {% render_bundle 'bodega' 'js' attrs='async' %} </head> <body> <!-- Root --> <main id="root">{{ html|safe }}</main> <!-- Redux State --> <script> window.__REDUX_STATE__ = {{ finalState|safe }} </script> </body> </html>

We can now test the interaction between Node and Django. Let’s start the Node server and the Django server, open up a browser, and go to the url that corresponds to our sandwich view. To prevent our React frontend from taking over the page on load, we’ll disable JavaScript in DevTools. If you see a page with the output that you defined in your render and buildInitialState functions, then all is well.

Defining the Render Function

It will be instructive to first look at the code of the render function and then to explain how it works.

// render.jsx import React from 'react' import { Provider } from 'react-redux' import { match, RouterContext } from 'react-router' import ReactDOMServer from 'react-dom/server' import configureStore from '../bodega/src/scripts/store/store' import getRoutes from '../bodega/src/scripts/components/routes' export default function render (url, initialState) { const store = configureStore(initialState) const routes = getRoutes(store) let html, redirect match({ routes, location: url }, (error, redirectLocation, renderProps) => { if (redirectLocation) { redirect = redirectLocation.pathname } else if (renderProps) { // Here's where the actual rendering happens html = ReactDOMServer.renderToString( <Provider store={store}> <RouterContext {...renderProps} /> </Provider> ) } }) if (redirect) return render(redirect, initialState) // Fun recursion const finalState = store.getState() return { html, finalState } }

The first thing the render function does is configure the Redux store. I used the same configureStore function that I had already defined in following the usual Redux API pattern.

The second thing the render function does is get the frontend routes of my React app, by calling a function I wrote called getRoutes. This function takes the Redux store as an argument and returns all of the routes to my app. It prevents code duplication because I can call it in both server and browser environments (See the Handling the Client Side section below to see how it is used in a browser environment).

The name getRoutes, though accurate, is somewhat incomplete. The function does not just get routes. It also gets the React components of which my app is composed, since they are embedded in the definitions of the routes themselves. Therefore, the getRoutes function is what links my existing React app to the render function.

Next, in order for the render function to match the desired route, I use React Router’s match function. This function’s first argument is an object containing all of my app’s routes as its first key — which we have from the getRoutes function — and the desired route as the second key. The match function’s second argument is a callback that gets evoked after matching is complete. In a successful matching, this callback’s third argument is a renderProps object. These renderProps represent the state of my app’s props at a given route. I pass this object into React-Router’s <RouterContext> component (which is a static version of its more familiar <Router> component) to render the state of our app at the matched route.

To give the components of my app access to the Redux store, I wrap the <RouterContext> component with the <Provider> component from the React-Redux library.

Next, I call ReactDOMServer#renderToString with this wrapped component as its argument to render the state of my application at the matched route to HTML.

Finally, I call getState on my Redux store to extract its final state in case the rendering process changed anything.

If the match function fails to match the desired route, the second argument of its callback is a redirectLocation argument. In this case, I recursively call the render function with this new desired route. I am confident that there will never be a chain of infinite redirects because I have defined a wildcard route to handle such cases.

Calling the Render Function

The render function will not work as it is currently defined. The reason for this is that the JSX used in the function itself, as well as in the rest of my app, is not understood in Node runtimes. Therefore, I use Webpack and Babel to transpile my render.jsx file into Node compliant code. All I had to do to make this work was to copy my existing webpack config, change the entry point to render.jsx, and replace the target parameter with target: ‘node’.

When transpiling, I ran into some errors. Since this version of my React app will not be running in the browser, window and document will not be defined. Therefore, I had to move all references to window and document to functions that are executed only after the DOM is accessible. This involved moving references to window and document from methods like Component#constructor to methods like Component#componentDidMount. Unlike Component#constructor, Component#componentDidMount will only be called after the component has been mounted to the DOM. I also had to abandon some third-party libraries that relied on window or document in problematic places.

Handling the Client Side

Now that my server responds with a fully rendered page of my app, I need to adjust my client side JS to expect this. Here’s the code I wrote.

// entry.js import React from 'react' import ReactDOM from 'react-dom' import { match } from 'react-router' import { Provider } from 'react-redux' import { Router, browserHistory } from 'react-router' import configureStore from './bodega/store/store' import Root from './bodega/components/root' import getRoutes from './bodega/components/routes' import './styles/main.scss' if (document.readyState === 'loading') { document.addEventListener('DOMContentLoaded', initializeApp) } else { initializeApp() } function initializeApp () { const store = configureStore(window.__REDUX_STATE__) const { pathname, search, hash } = window.location const location = `${pathname}${search}${hash}` const routes = getRoutes(store) match({ routes, location }, () => { ReactDOM.render( <Provider store={store}> <Router history={browserHistory}> {routes} </Router> </Provider>, document.getElementById('root') ) }) }

You might have noticed that I added an async attribute to my script tag in base.html. The async attribute makes the tag non-render-blocking, which means that the browser won’t wait for the entire script to download before rendering. This produces a considerable speed increase, especially with large JavaScript bundles. However, it also means that it is possible for the script to be executed at any time during the load process, which means that the standard procedure of waiting for DOMContentLoaded before rendering with ReactDOM might not always work, since DOMContentLoaded might have already fired, in which case, the React app would never get executed and the page would never become interactive. Therefore, I check the document.readyState when the bundle is initially executed. If the readyState is complete or interactive, I initialize my React app right away. Otherwise, I add listener for DOMContentLoaded and use my initialize function as the callback.

In my initializeApp function, I get the current state of the Redux store from the window and pass it into configureStore to setup Redux. Next, I match the current route, just as I did on the server side, using the same getRoutes and match functions which I discussed above. Instead of calling ReactDOM#render, which is the usual pattern in client rendered apps, I call ReactDOM#hydrate, which sets up React’s virtual DOM and installs listeners to make the page interactive.

Conclusion

Since deploying this project, we have seen much better SEO at Meural. Now a Google search for the terms meural and some artist’s name will yield a result of that artist’s page or one of her playlists, if that artist is in our collection. Prior to this deployment, this was not possible, since we had exposed only one webpage, which contained our single-page React app.